For the past sixty years, the modern farmworker justice movement has been at the forefront of advocating for the rights of farmworkers in the United States. For good reason, the history of the farmworker justice movement is most commonly associated organizationally with the United Farm Workers and regionally with California. While César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and the UFW are the towering figures and union historically identified with the struggle for Latinx farmworkers, this narrative erases the Midwestern activists and organizations that have been instrumental to shaping some of the most forward-thinking developments within the farmworker justice movement. Who are the organizations and activists that have been at the forefront of the Midwest’s farmworker movement? What insights emerge when the Midwest is brought to the center of the farmworker justice movement’s history? What is the current state of the farmworker justice movement? These are the three questions guiding my second book project.

Where is the Midwest in the History of the Farmworker Justice Movement?

Key Findings

A fuller accounting of the farmworker justice movement requires the U.S. Midwest (and South) to be at the core of these new interpretations.

During the period that the United Farm Workers are declining in national influence, a Midwestern agricultural union, the Farm Labor Organizing Committee, is transforming the farmworker justice movement.

Despite dramatic changes within agribusiness – including mechanization and biotechnology, labor sources, and global agricultural output transformation – many of the core issues that animated the modern farmworker justice movement in 1960s have yet to be fully addressed.

Federal Labor Legislation and Farmworkers

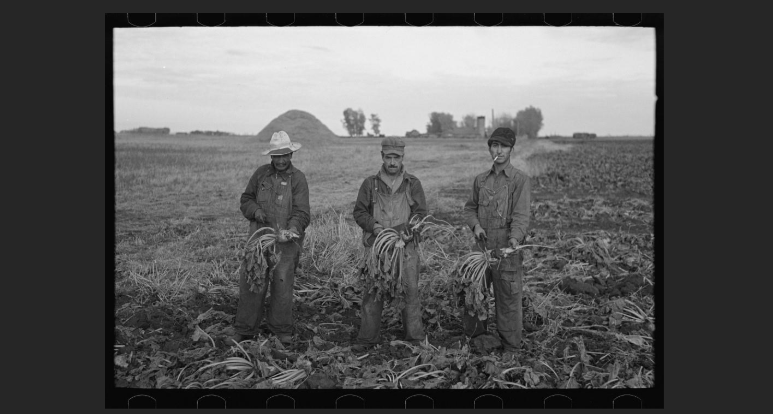

As of June 2025, there are over two million migrant and seasonal farmworkers in the United States. These workers are essential to this country’s $1.053 trillion food and agriculture industry.1 Much of the socioeconomic inequality, occupational hazards, and overall vulnerability of migrant farmworkers in the U.S. is the result of the fact that farmworkers are specifically excluded from the basic protective labor laws that workers in all other industries receive. This agricultural exceptionalism is most visible in National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which was passed in 1935.The NLRA guaranteed collective bargaining power to all workers in the U.S.However, farmworkers were specifically excluded from the federal right to collectively bargain free from retaliation, such as being fired. Consequently, it was left up to the states to allow farmworkers to form unions to collectively bargain. Another example is the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA),which provides minimum wage, maximum hours before overtime pay, and child laborprotections for workers. Originally excluding coverage for agricultural workers, it was not until the 1960s that the FLSA was amended to include minimum wage and child labor protections for agricultural workers.2

The Farmworker Justice Movement

In California, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) was formed in 1959 and led by Larry Itliong. Largely consisting of Filipino-American farmworkers, Philip Vera Cruz, Ben Gines, and Peter Velasco were also crucial in AWOC’s recruiting and organizing efforts. César Chávez coordinated the National Farm Workers Association’s (NFWA) first official meeting in 1962. In 1964, Chávez took over as president, while Gilbert Padilla and Dolores Huerta served as co-vice presidents. In 1965, AWOC led a series of strikes against grape growers in Delano, California. Shortly thereafter, the NFWA and their predominantly Mexican-American farmworkers, struck alongside AWOC. In 1966, AWOC and NFWA combined to create the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, more commonly referred to as the United Farm Workers (UFW). In 1970, the persistent, five-year strike and boycott efforts paid off. Delano growers signed a historic agreement with the UFW, ending the Delano grape strike.3 While this was the end of a particular episode in the UFW’s history, the union would face more aggressive challenges throughout the 1970s. By the end of the decade, the UFW was largely in a state of decline. This was a current that would only continue in the 1980s as the union was weakened by anti-union politics, internal disagreements, the loss of leadership, and depletion of union contracts.

The Farm Labor Organizing Committee

In 1967, one year after AWOC and the NFWA merged into the UFW, Baldemar Velásquez and a small cadre of midwestern migrant farmworkers formed the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC). At the moment that the UFW’s influence was declining, FLOC began to establish a foothold in the Midwest and directly challenged the ability of corporate food processors to evade responsibility for the conditions of migrant farmworkers. In 1986, Velásquez and other FLOC organizers innovated a three-way agreement that linked the interests of the three main parties involved in Midwestern agribusiness: migrant farmworkers, growers, and the corporations. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, FLOC successfully challenged some of the country’s most recognizable and powerful corporate food processors – Campbell Soup Co. and Heinz. FLOC’s accomplishments in the 1980s transformed the landscape of organized labor and agribusiness. While reactionary politics, weakened labor laws, and economic transformations created a challenging environment for labor during the late-twentieth century, FLOC succeeded in securing union contracts for Latinx migrant farmworkers in the Midwest.

Conclusions

The history of the farmworker justice movement in the U.S. appears radically different when the UFW is decentered, and further attention is reoriented toward FLOC. The periodization of the farmworker struggle must be rewritten when FLOC is elevated to a position of prominence within this economic, political, and social movement. The history of the FLOC, much like the history of the Midwest within the fields of Mexican American and Latinx history, has remained peripheral despite its extensive contributions to these histories.

Meet the Researcher

Juan Ignacio Mora is an Assistant Professor of History and Latino Studies. He was a CRRES Postdoctoral Fellow from 2021-2023. Before that, he received his PhD from the Department of History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His current project, Latinx Encounters: How Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Puerto Rican Made the Modern Midwest, is forthcoming with the University of North Carolina Press’ Latinx Histories series.